Okay, look. Empir. Evidence-Based Research. EBP. Buzzwords plastered all over grant applications, conference banners, and university mission statements. Sounds pristine, right? Like this gleaming cathedral of pure, unadulterated truth built brick by statistical brick. We\’re supposed to bow down, chant \”p<0.05,\" and accept the verdict. But let me tell you, down here in the trenches, where the pipette tips overfloweth and the code just won\'t compile? It feels messier. Way messier. And honestly? Sometimes it feels like trying to build IKEA furniture with half the instructions missing and a toddler swinging the allen key.

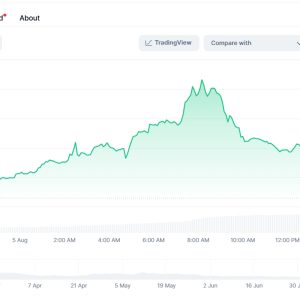

I remember this one project, early on. We were looking at this intervention for reducing post-op pain. Animal model, promising preliminary data (translation: it kinda-sorta worked twice in a row). Designed the study meticulously – blinding, randomization, the whole nine yards. Felt like a proper scientist. Ran the stats, heart pounding a bit… and bam. Nothing. Zilch. Nada. The beautiful, clean lines on my pre-registered analysis plan met the messy reality of biological variation, technical hiccups (did that one batch of reagent feel off? Probably.), and just… noise. The null hypothesis laughed in my face. I sat there at 3 AM, caffeine jitters meeting a profound sense of deflation, staring at the flatlined graph. \”Evidence-Based\” felt like a cruel joke. Where was the \”based\” part when my beautiful hypothesis was face-down in the mud?

That\’s the first practical application of empiricism they don\’t always emphasize in the shiny brochures: Humility. Brutal, ego-crushing humility. It’s not just about accepting the data when it confirms your brilliant idea. It’s about staring down the barrel of insignificance and not immediately reaching for the \”Well, maybe if we subset the data like this…\” button. It hurts. It feels like failure. But that’s the bedrock. If your evidence-based practice doesn’t start with the gut-punch acceptance that you, personally, your beautiful theory, might just be spectacularly wrong… you’re already off track. It’s not just methodology; it’s a state of mind. A deeply uncomfortable one.

Then there’s the translation game. Let’s say you do get a positive signal. Great! Now try explaining your meticulously controlled, double-blinded RCT findings to a clinician who’s been using Method X for 20 years based on… well, vibes and that one case that went really well back in ’05. Or worse, a hospital administrator whose eyes glaze over at \”confidence interval\” but light up at \”cost-saving.\” The practical application here isn\’t just the science; it\’s the alchemy of turning dense stats and protocols into something tangible, something that fits into the chaotic, time-pressed, resource-starved reality of actual practice. It’s about understanding that \”evidence\” isn\’t a magic wand you wave. It’s a conversation starter, often a difficult one, fraught with inertia, tradition, and frankly, sometimes, defensiveness. You need the evidence, sure, but you also need the diplomacy of a seasoned negotiator and the patience of a saint. Some days, I feel like I possess neither.

And the tools? Don\’t get me started on the tools. Systematic reviews? Love \’em. In theory. The gold standard! Until you spend three weeks wrestling with five different databases, crafting Boolean search strings that feel like incantations, only to realize half the relevant studies are locked behind paywalls thicker than the Berlin Wall, and the other half used outcome measures so bizarrely specific they\’re practically useless for synthesis. Meta-analysis? Powerful magic. Also prone to producing garbage if the studies going in are garbage (GIGO is the real law of the universe, forget gravity). Or when heterogeneity is so high the forest plot looks like a… well, a forest after a hurricane. The practical application involves a lot of swearing at software, existential dread about publication bias, and the constant, low-grade anxiety that you’re missing something crucial buried in some obscure conference abstract from 1998. It’s meticulous, often tedious work that feels miles away from the \”Eureka!\” moment.

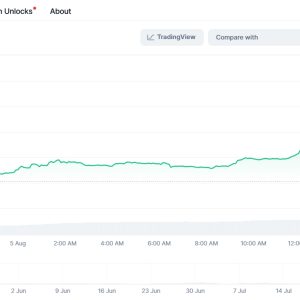

Then there’s the speed. Or lack thereof. The world moves fast. Problems evolve. New tech emerges. But building a solid evidence base? It’s glacial. Designing a decent study takes ages. Recruitment? An eternity. Analysis? Don\’t rush it, for the love of all that\’s holy. Peer review? A black hole where time dilates. By the time your beautiful, rigorous paper lands in a journal, the clinical question might have shifted, the context changed, the initial urgency faded. The pressure to \”just do something\” is immense, especially when things are urgent. Waiting for perfect evidence feels like a luxury we can\’t afford. But jumping in without any? That’s how we got into half these messes in the first place. This tension – between the need for timely action and the slow, grinding wheels of robust empiricism – is a constant, gnawing ache in this field. There’s no easy answer. Just… discomfort.

Remember that antidepressant scandal? Well, maybe scandal is strong, but that big 2017 BMJ paper digging into publication bias? How positive results got shouted from the rooftops while negative or inconclusive ones got filed away in the \”Drawer of Doom\”? That wasn\’t just academic gossip. That skewed the entire evidence base doctors were relying on for years. Made things look way more effective and safer than they perhaps were. The practical application lesson screamed from that mess? Transparency isn\’t optional. Pre-registration. Sharing protocols. Publishing null results even when they taste like ash in your mouth. Making data available (within ethical bounds, obviously). It’s about building trust, yes, but also about building an evidence base that isn\’t fundamentally distorted. It requires overcoming inertia, fear of looking bad, and sometimes, institutional resistance. It\’s work. Hard, often thankless work. But seeing how easily the whole edifice can tilt without it? Terrifying.

So, is it worth it? This messy, frustrating, ego-bruising, slow-motion slog? Honestly, some days? I stare at the mountain of emails, the rejected grant application, the ambiguous pilot data, and think… maybe not. Maybe vibes are easier. But then I remember the alternative. The decades of bloodletting, the thalidomide babies, the treatments inflicted based on authority, charisma, or just pure guesswork that caused real, lasting harm. The weight of that history lands heavy. Empiricism, evidence-based practice… it’s not about finding perfect, immutable Truth with a capital T. It’s the least worst method we’ve got. It’s a process, a constant course-correction, a way of systematically reducing the probability we’re full of crap. It’s hard, often deeply unsatisfying work, riddled with uncertainty and compromise. But the alternative – flying blind, trusting gut feelings over data, repeating the same mistakes because \”that’s how it’s done\” – that’s a luxury we absolutely cannot afford. Not when real people, real lives, are on the line. So yeah, I guess I keep showing up, allen key in hand, squinting at the confusing IKEA instructions of reality. Not because it’s glamorous, but because the alternative is genuinely scary. And maybe, just maybe, we inch a fraction closer to something resembling understanding. Maybe.